Many

people have asked me to write this book: After a sleepless night beset

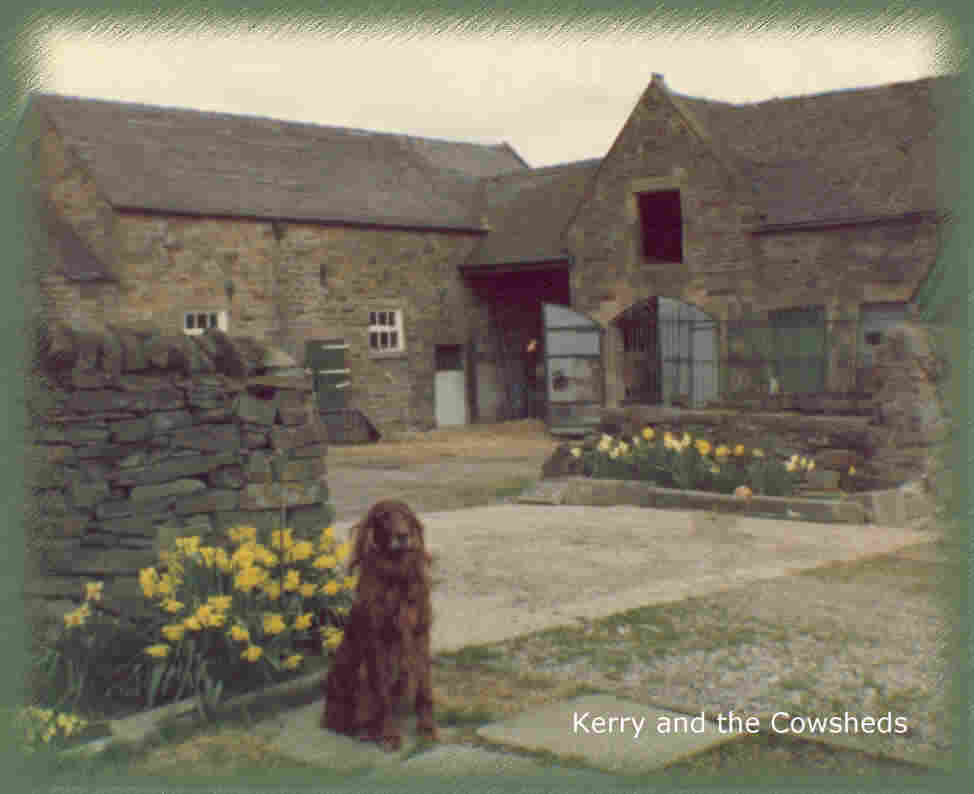

by the twittering of sparrows and starlings, and gentled by the coo of

doves from the cowshed roof, the morning chorus bids me rise and start

to write. Kerry Gold our lovely red setter dog is asking to go outside.

I must make a cup of coffee, see how yesterday's new calf is. What are

those woolly jumpers, the sheep bleating at, a fox or a stray dog perhaps?

Many

people have asked me to write this book: After a sleepless night beset

by the twittering of sparrows and starlings, and gentled by the coo of

doves from the cowshed roof, the morning chorus bids me rise and start

to write. Kerry Gold our lovely red setter dog is asking to go outside.

I must make a cup of coffee, see how yesterday's new calf is. What are

those woolly jumpers, the sheep bleating at, a fox or a stray dog perhaps?

Alas, being a mere woman I feel genius is already getting spent, ere I

put my pen to paper. I will just stir the banana wine and thank God it

rained so I cannot go raspberry picking today, so I had better get writing.

What shall I call this book?

It

is about survival in its many aspects, the strength and brightness of

the human spirit, which enables us to come, through trauma and live in

hope. For them and for all survivors I shall call my book. "Reach

for a Rainbow" as life indeed, is sun filtered through the rain,

a vision, and a rainbow in the sky. I am sure that all families will be

able to Identify with our struggle to help each other through desperate

circumstances.

Thirty eight days shipwrecked with my family, alone in the Pacific Ocean.

Our strengths and frailties exposed, stripped of everything but our fierce

determination to survive and bring our children home, and there to live

ever after with the trauma of this experience.

Come with me to the Pacific wastes, and I will tell you of how I drew

from the wealth of experience in my childhood and early motherhood on

a farm, and how these memories constantly sustained my courage and spirit

to carry on and finish what we had started together.

We could not end our children's lives there in that little boat!

Chapter 1

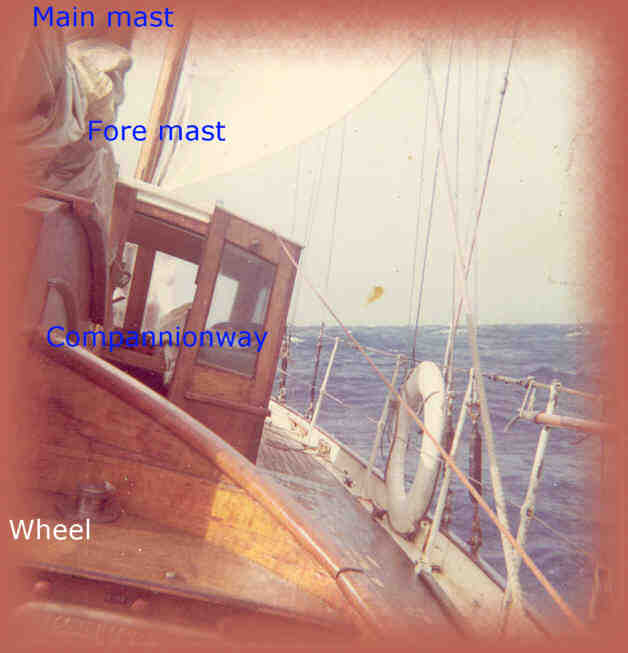

The

dirty bilge water swilled over the cabin floor where I lay: black and

evil it streamed, a mixture of seawater and diesel through my long fair

hair. I opened my eyes; the long miserable night was over!

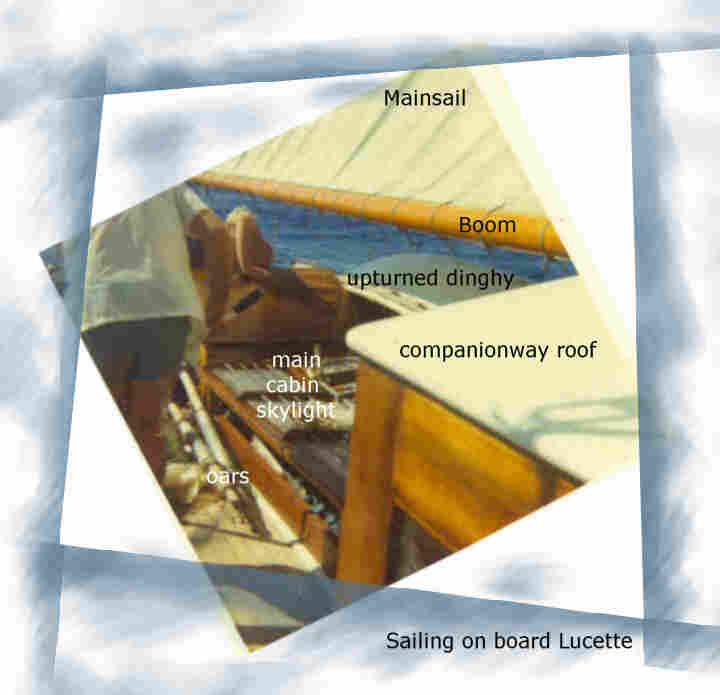

The blue linoleum with its brass fastenings on the floor

was still there, only in close up. Lucette had been slattering about as

if she didn't want to go anywhere eith er.

The aftermath of a rough night's sailing strewed the floor, waiting for

me to clean once more. So much useless effort and I felt very tired. It

had been impossible to sleep in the bunk. Rolling and pitching in the

heavy seas on our first night out of the Galapagos Islands had left me

feeling very sick and the floor was still coming up to meet me.

er.

The aftermath of a rough night's sailing strewed the floor, waiting for

me to clean once more. So much useless effort and I felt very tired. It

had been impossible to sleep in the bunk. Rolling and pitching in the

heavy seas on our first night out of the Galapagos Islands had left me

feeling very sick and the floor was still coming up to meet me.

I struggled to stand up; I lit the paraffin stove to heat up the cold

rice left uneaten from the previous night. It smelled vaguely of paraffin,

but they would eat it if they were hungry and no one would complain, but

it was definitely a black tea and fresh lemon day for most of us. I cleared

the galley area, washed my precious kitchen knife, carefully placing it

on the blue Formica top. I wondered who would be the next person to take

it away and lose it once more.

It

was almost I0 o'clock and not a glimpse of sun that day. Dougal my husband

was up above trying to take a sight. He came below to work out a position

and as he passed on his way to the aft cabin he put his arm around me

and said. "What's the matter Lyn?"

I laid my head on the safety of his shoulder for a moment and answered,

"I feel as if I don't want to go any further, not even an inch."

He reassured me with promises of better days to come, sailing the Pacific

Ocean in the ease of the trade-winds. Our next port of call the beautiful

Marquisa Islands, Tahiti, and then hopefully finding work in New Zealand.

I

had always worked. Years and years of it, and had recently completed six

months at the Cedars of Lebanon hospital in Miami, where I was on night

duty; in charge of the delivery unit.

Would there never be time for anything but work? No time to sit in the

sun with nothing to do, but enjoy the companionship of the people I loved,

and watch our twelve year old twins grow up. We smiled at each other,

yes; surely the best was yet to be. Sailing free before the trade-winds

together; cruising into the Pacific Ocean and on to our destiny. I went

off happily to change from housecoat and clean my teeth: I heard young

Sandy on watch shout,

"Whales!" "Whales!"

I called to Neil and Robin who were resting in the fo'c'sle bunks, something

for them to see I thought, as I started to clean my teeth.

A sudden shuddering crash from beneath my feet as a jet of water hit the

ceiling with great force, and then came down on my head. I screamed, as

I gazed in horror at the blue sea pouring through the hole at my feet,

along with bright daylight. Lucette seemed to have come to a jarring mind

bending stop. I ran, closing the toilet door tightly behind me.

'We're sinking!' I shouted to Dougal as with all speed I hurried Neil

and Robin (our extra passenger) on deck. I felt electrified into action

almost as if I had known we were going to sink. I went aft to the top

drawer of the bunk where I kept all the valuables.

Dougal was in the  gangway

trying to stem the torrent of water pouring in through the weak garboard

strake. He called for pillows to stem the tide,

gangway

trying to stem the torrent of water pouring in through the weak garboard

strake. He called for pillows to stem the tide,

"It's no use" I answered "there's a big hole up for'ard

and we are sinking." He looked at me in disbelief. "Come on

Dougal" I entreated him, but he stoically continued to push things

against the impacted holes; and tried to replace the bilge, I ran up on

deck to join the others. Douglas was already standing by the life raft

"We're sinking" I said to him "Get the raft off!",

"No! Wait for Dad"I gave out the life jackets as Robin called,

"What can I do?" "Guard this with your life," I said

as I gave him the five-gallon drum of drinking water.

I heard cries of "Where's Dad? Where's Dad?" Hell! Where was

he? "Dougal! Dougal!" I shouted down the companionway "Come

quick she's going." I looked down into the cabin; there he was chest

deep in water, wading slowly towards the bottom rung of the steps, and

wonder of wonders! He held aloft the precious knife. I breathed a great

sigh of relief at the sight of him.

l"Are we sinking Dad?" said Douglas "Yes son, I'm afraid

so" came the reply. Douglas heaved the life raft over the side of

Lucette. Dougal cut our dinghy the Ednamair, free.I stood mesmerised for

a moment as if watching a film unfolding in slow motion.

Neil,

who had put the teddy bears up his t-shirt, jumped straight over the rail

and was already in the sea looking up at me and shouting

Neil,

who had put the teddy bears up his t-shirt, jumped straight over the rail

and was already in the sea looking up at me and shouting

"Mum the teddy bears got drowned."

Neil was back in the sea. The deck was awash now. Lucette's bow was disappearing

fast. I struggled to climb over the rails but neither of my legs would

go over. I looked for Dougal. There he was standing in the water at the

bow, his back towards me, and in a loud voice declared, "Abandon

Ship!"

As he slipped into the sea, I thought, as the water took me roughly through the rails "but there is no one aboard!"

I

swam towards Neil. My toes curled under as I thought of the possibility

of the Killer Whales amongst us. I reached 'Ednamair', (the dinghy) to

which Neil was clinging and Robin holding on to the painter, I was using

my arm to hold on when Dougal called "No, not there, you'll swamp

it." I looked around, "Well where the hell else could I go?"

I thought, the Pacific's a big place. First wave on the left or what!

I looked back to Lucette but she had taken her final curtain and sailed

straight on under the sea .

Poor noble Lucette, she had given us time to get off and taken with her

our talisman, the caul of a baby I had once delivered; it had been given

to me by the mother at my request.

.

Poor noble Lucette, she had given us time to get off and taken with her

our talisman, the caul of a baby I had once delivered; it had been given

to me by the mother at my request.

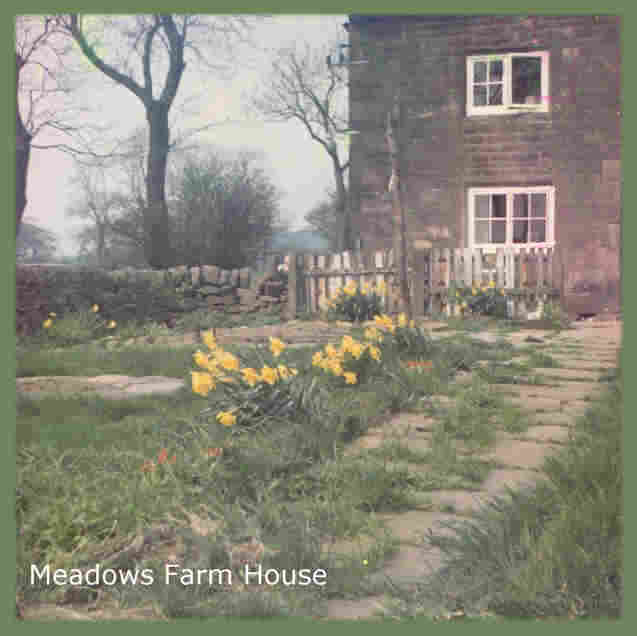

It had dried a paper thin membrane hanging on an oak beam in our old home

at Meadows Farm. A long ago superstition of fisher folk, whose belief

it is, that you will never drown at sea if you carry one.

I

thought of the story of my own eventful birth at a place called Butterton

on the Staffordshire moors. My mother told of how father was working nights

at the copper foundry, while her sist er

and a neighbour stayed with her. It was dark when mother went into Labour,

and her sister and neighbour were both too frightened to go alone to fetch

the doctor. They walked four miles together leaving mother alone with

two little children and me, who arrived quite unaided into this world;

'Bawling my head off' and still attached to my mother, had made my own

way to the bottom of the bed taking half the placenta with me.

er

and a neighbour stayed with her. It was dark when mother went into Labour,

and her sister and neighbour were both too frightened to go alone to fetch

the doctor. They walked four miles together leaving mother alone with

two little children and me, who arrived quite unaided into this world;

'Bawling my head off' and still attached to my mother, had made my own

way to the bottom of the bed taking half the placenta with me.

Old Dr. Hall arrived by horse and carriage having stopped at the Vicarage to pick up Mrs. Chestle who assisted with his midwifery cases for a charge of thirty shillings. He found mother lying in a massive haemorrhage too weak to move. This was my first lesson in how to fend for myself. The caul had had served its purpose and here we all were.

Dougal

at the opening of the rubber raft, directing the traffic I thought as

he called."Send Neil across! Now you! Now Robin", and he fastened

the dinghy painter to the raft.

We were all together again. Oh! Where was Douglas?The last time I saw

him he was about to put his finger in the exhaust valve of the raft (where

the excess air was escaping with a loud noise) and he had called frantically

to me, "Mother! Give me a patch"

I looked round the ocean for something that would do. I said "Will

this do?" as I threw him an orange, he gave me a look as if to say

"Only mother would be stupid enough to give me an orange"

"Douglas!" "Douglas!"We all shouted and he came to

the entrance with his beaming face alight,"Look what I've found,"

Treasure indeed. I thought as he produced a spool of fishing line to which

was attached the Genoa sail, washed off Lucette's deck.

We were all togeth er

again in our new home Robin had gallantly offered to go after the water

drum but Dougal had thought it too great a risk and we sadly watched it

float away into the distance.

er

again in our new home Robin had gallantly offered to go after the water

drum but Dougal had thought it too great a risk and we sadly watched it

float away into the distance.

Killer Whales" someone said, "thirty of them!" " One came up bleeding from its head!"; "Perhaps the others have eaten it!" "I hope so" Sandy remarked. "I wonder if they are still outside." We stopped speculating and I remembered eerily the cold feeling of close eye contact with a Killer Whale, through the viewing window at the Miami Seaquarium it looked as if it was saying, "I'll get you for this, this eternal captivity." and I had left with a most uncomfortable feeling for it's lost freedom.